|

| Pendragon's Caledonia from Beyond the Wall |

As described in "

The Road to Englandia," after too many years of studying history, science, and so on, I need my game world to have a lot of verisimilitude and depth to it or I find it unsatisfying, so in 1997 Beverly (my history-major wife) and I settled on the British Isles in the year 1000 as the base setting for my gaming campaigns.

(Extreme verisimilitude is not something I require when I'm a player, just when I'm running games, because the internal coherence makes it much easier for me to think on my feet about what might happen next. As a player, I don't need those crutches, since the character's personality and understanding of the world are all I need to figure out what to do next. I can play in much less grounded worlds than I can run, oddly. YMMV.)

Over the past eighteen years, I filled two bookcases with reference materials to help flesh out my understanding of that time and place (Anglo-Saxon Books has been a godsend). Although some would find this a chore, for me it's a pleasure, since I love to learn and am relieved when the game does not distract me with too many anachronisms—other than those I put there myself on purpose, to advance the fun in the game. As with a poet who writes haikus or other structured poems, I find the structure and limitations imposed by the details of what we know about this setting stimulates my creativity about the many, many things we don't know. They don't call it the Dark Ages for nothing.

For a year I set Englandia adventures in the rural lowlands of Cheshire, but for the following nine years they were south in the Shropshire Highlands, near the border with Wales. I still think of those Shropshire adventures as my main Englandia game, despite not running anything there for eight years. I painted myself into a storytelling corner with too many non-player characters at a Jane-Austen-meets-Beowulf social dance with a lot at stake. Then my nonprofit ate my life, leaving me too few spoons after work to solve the problem, though I've known for years what the solution has to be.

|

| Wikipedia's map of the Hebrides |

I still think of those Shropshire adventures as just paused, so for the new and different dungeon-based adventures I planned to start a few years ago (after reigniting with excitement from reading all the wonderful old-school renaissance posts about dungeon design and the mythic underworld) I did not want them to take place anywhere near Shropshire, to reduce the odds of cross-contamination of the adventures.

Looking for isolation, I found it in the far North, which led me to Greg Stafford's marvelous supplement

Beyond the Wall, which describes North Britain for his magnificent role-playing game

Pendragon. If you're going to do Dark Age historical gaming in the British Isles, you need

Pendragon, which is brilliantly constructed, meticulously researched, and beautifully mapped, with gazetteers full of concise place descriptions as stimulating as the best work Judges' Guild ever put out for their

Wilderlands of High Fantasy supplements.

My players tend to be a bit disruptive—the Shropshire campaign has so far accidentally set two enormous, angry, warring dragons upon Normandy, which is currently in flames, and refugees are fleeing all over Europe and so unlikely to invade England in another sixty-five years, oops—so even with the help of the physical dimensions of dungeons to constrain them, I wanted to place this new cycle of mythic-underworld adventures someplace isolated even from the isolated places, to limit the damage.

Thus, I turned from the mainland of Scotland and Pictland to the islands, quickly settled on the Hebrides, and dubbed this new cycle of dungeon-based adventures Islandia. After all, the history of the Hebrides at this time was already so disrupted that historians and archaeologists are still struggling to piece it all together, like a dark age within a Dark Age, so those lacunae can cover a lot of player-induced chaos, allowing the mainland of Britain to still stay enough on course to leave me an intuitive baseline to work with for what's happening when the players aren't around.

Some of the first fantasy novels I read as a child were C. S. Lewis's

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and Ursula LeGuin's

Earthsea Trilogy, and British Celtic legends are packed with moody seascapes, mysterious islands that come and go, and hollow hills. I could at once see how this setting could greatly enrich gaming in the mythic underworld, inspiring changes in the modules that would make them less generic fantasy, more a unique experience for the players and me.

To avoid cross-contamination from the increasingly epic Shropshire adventures, to create the space needed for these mythic-underworld adventures to develop their own flavor, I also isolated them temporally. The Shropshire cycle had advanced up through 30 June 1001, so I reset the Islandia games back to mid-Spring 1000, before my players upended the table on history.

|

| Campaign map of Skye, based on Wikipedia's topographical map |

With the general time and place set, it was time to dial in and place where

In Search of the Unknown could best take place.

Of the Hebrides choices,

Beyond the Wall's gazetteer described the most adventure material for Skye. Google searches revealed this was no anomaly. Skye is packed with ancient brochs, cairns, duns, ghost villages, and other material ripe for fantasy gaming development, and Skye has a rich tradition of documenting their folklore. It was an embarrassment of riches, so Skye was the obvious choice.

The combination of small population (to avoid the players' disruptive powers being too early inflicted upon a population center), central location, and a pleasant writeup in

Beyond the Wall (which we won't be sharing with my players yet, because the details of that gazetteer entry have not yet come into play for the party) led me to the small village of Drynoch on Loch Harport, on the north edge of The Minginish peninsula. Our first game walkthrough, which we'll start in my next post, takes place in what passes for a public house in wee Drynoch. And as a small reference to

A Wrinkle in Time—another early read, courtesy of my fourth grade teacher, Helen Yorozu, at Emerson Elementary School in South Seattle—it opens with a blustery, stormy day; anything or anyone might blow into town on such a day, even—gasp—player characters!

I started with some fairly empty maps of Skye to work with, which was fine at first because the players were going to have their hands full dealing with their immediate environs, but after a little over a year of gaming I finally broke down and built the above campaign map of Skye, capturing all the ancient settlements and structures I could. Drynoch's isolation from big (well, "big"; this is Skye, not Yorkshire) population centers in 1001, already evident to me before I built this map, is nicely visualized here. I have no way of knowing if Drynoch existed at all back then, since William the Conqueror's

Domesday Book—so useful to my Shropshire adventures—never reached this far north, but that works in our favor, too, since it leaves us free to invent, so long as we retain verisimilitude and internal consistency.

|

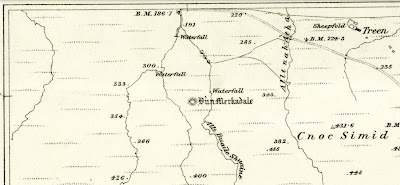

| Ordnance Survey map of the vicinity of Drynoch, showing Dun Merkadale |

Great Britain's lovely and indispensable Ordnance Survey maps let me scout the immediate environs of Drynoch from the comfort of my home. Even though much has changed in the past thousand fifteen years, it's surprising based on the

Domesday Book how much has not. Unlike America, which lost a lot of its history in the Great Plague and subsequent conquest of the Native Americans, Great Britain's history is deep. Wee villages and even the boundaries of fields have in many cases remained stable for twelve hundred years or more, so even a modern map like this is very helpful, when seen after spending years comparing modern Ordnance Survey maps to the

Domesday Book.

|

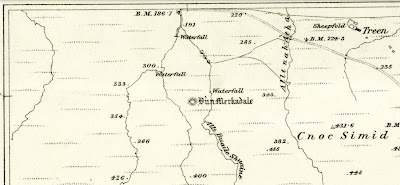

| Ordnance Survey Map of Dun Merkadale |

In keeping with our haunted-isles-and-hollow-hills theme for the Scottish mythic underworld, I chose the nearest dun—Dun Merkadale as the setting for my take on

In Search of the Unknown.

The Ordnance Survey website also includes an option to look at the same location using some of their earliest maps, which date back a century or two. Those maps are

much closer to the geography of 1000, with a lovely look and feel, and make valuable gaming references if you're lucky enough to be running games in the British Isles.

For my Shropshire games back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, I ordered both folding and rolled up maps to cover the areas we were gaming in. Seeing the locations of copses, wells, streams, cliffs, and ruins is extremely stimulating to story- and scenario-production when gaming, so it's a good investment if you're going to stick with a setting.

I've not yet made that investment for these adventures based on

In Search of the Unknown because the remarkable professionals at Ordnance Survey somehow never got around to mapping the hollow hills and other settings of the mythic underworld with the same level of attention to detail and professionalism they brought to the surface world of mere mortals—and who can blame them, since the lands of the fae are so often difficult to pin down—so for the players' home base and other aboveground needs, captures of online maps are all we need for now.

I'm sure many of you are bemused by the absurd lengths to which I went to choose the setting for a module that originally had almost no description of the surrounding area, but I had good reasons. First, that very absence was noted by several reviewers of the module as a weak spot and was among the reasons Gary Gygax replaced it in the

Basic D&D sets with B2

Keep on the Borderlands, because sandbox play is a fun element of D&D but it demands a sandbox, which B1 failed to provide. Second, just as the wells and springs and ruins on the Ordnance Survey maps for the Shropshire Highlands were creatively stimulating, so the details of this choice of settings has already proven very fertile ground for me, as I knew it would. Third, though, as I noted at the outset, for me this is not work; it's fun. There's no right or wrong way to prep your games, so long as you and your players are having a good time. Do what works for you. This works for me.

And so, without further ado, starting next post, we'll begin to recount the tale of Mahdi al-Wali, Sorcha the Urchin, and Evadne Moon-Touched as they venture

In Search of the Unknown.